2022 State of Pay Equity Report

What is the Gender Pay Gap?

In observance of Equal Pay Day (March 15, 2022), Payscale has updated our Gender Pay Gap Report to answer the question “what is the gender pay gap in 2022?” with additional data on race to explore the intersectionality of pay inequity.

It should be noted that Payscale’s crowdsourced data weights toward salaried professionals with college degrees. When analyzing the gender pay gap by race, we restrict our sample to those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Our data isn’t as impacted by low-income hourly workers, so the gender pay gap reported by Payscale might be dissimilar to what is reported by other institutions for the gender pay gap of the overall workforce — especially in the current labor economy.

Since we have started tracking the gender pay gap, the difference between the earnings of women and men has shrunk, but only by an incremental amount each year. There remains a disparity in how men and women are paid, even when all compensable factors are controlled for, meaning that women are still being paid less than men due to no attributable reason other than gender. As our data will show, the gender pay gap is wider for women of color, for women at higher job levels, and for women in certain occupations and industries.

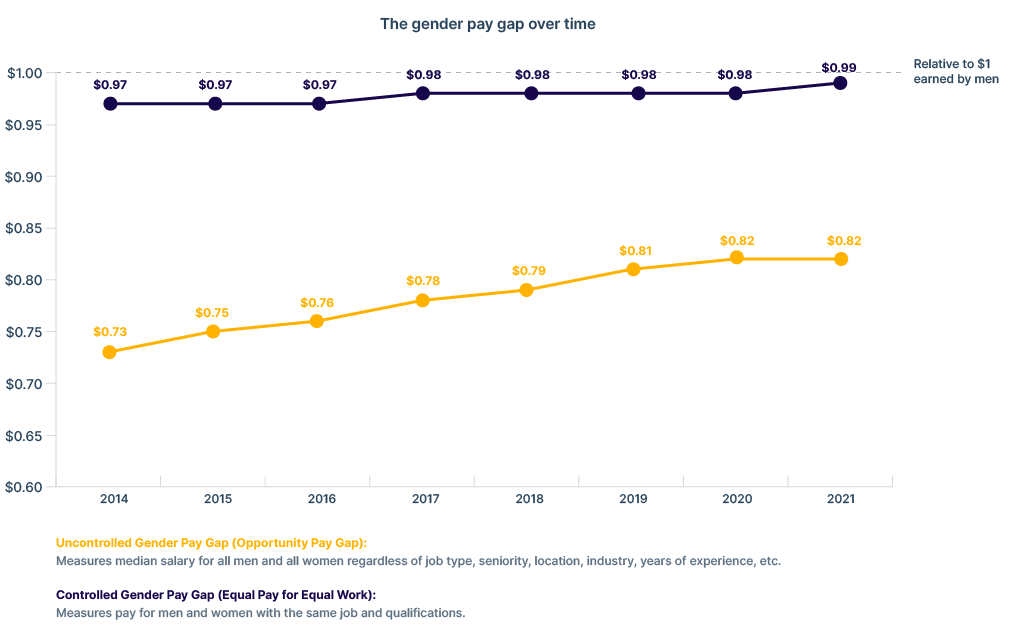

In 2022, the uncontrolled gender pay gap is $0.82 for every $1 that men make, which is the same as last year. Payscale’s gender pay gap report does not show that the uncontrolled gender pay gap has closed during COVID-19. If anything, closure of the gender pay gap during 2020 and 2021 reported by other institutions such as the National Committee on Pay Equity (NCPE) may be due to high unemployment, especially among lower wage workers, which artificially shrinks the gender pay gap. In subsequent years, the gender pay gap could widen.

The controlled gender pay gap is $0.99 for every $1 men make, which is one cent closer to equal but still not equal. The controlled gender pay gap tells us what women earn compared to men when all compensable factors are accounted for — such as job title, education, experience, industry, job level, and hours worked. This is equal pay for equal work. The gap should be zero. It’s not zero.

In other words, women who are doing the same job as a man, with the exact same qualifications as a man, are still paid one percent less than men at the median for no attributable reason. The closing of the controlled gender pay gap has been extremely slow, shrinking by only a fraction of one percent year over year. It has shrunk a total of $0.02 since 2015, but the shrinkage over the last year may not be reliable in the current economy.

Due to the economic turmoil of COVID-19, women — especially women of color — have disproportionately faced unemployment at higher rates than in typical years. When women with lower wages leave the workplace, it moves the median pay for women up — slightly closing the gap between men and women’s pay overall. When unemployed women return to work, they could face a disproportionate wage penalty from being unemployed compared to men, suggesting that the gender pay gap could widen again in subsequent years. However, this depends on the market and the pay women receive after unemployment.

In summary, we must be cautious about the gender pay gap appearing to close in the current economy.

The gender pay gap is closing over time but at glacial speed

Understanding the controlled and uncontrolled gender pay gap

The controlled gender pay gap measures “equal pay for equal work”. Both the uncontrolled gender pay gap and the controlled gender pay gap are important for understanding how society values women. The uncontrolled gender pay gap is an indication of what types of jobs — and the associated earnings — are occupied by women overall versus men overall. This in turn is an indicator of how wealth and power is gendered and the value that women have compared to men within our society.

Occupational segregation based on gender norms is one large driver of the overall pay differences between men and women. Unconscious bias informs what types of careers are “suitable” for women versus men, which are indoctrinated at a young age. For example, women are more likely to be in positions of service, education, healthcare support and other fields associated with “nurturing”, while men are more likely to be in positions of problem solving and wealth management. Women face wider pay gaps in male-dominated occupations and industries. In addition, when women enter occupational fields traditionally dominated by men, the pay for positions in those fields drops.

Men and women choosing different careers doesn’t mean that the uncontrolled gender pay gap is less meaningful than the controlled gender pay gap. The uncontrolled gender pay gap reveals the overall economic power disparity between men and women in society. Even if the controlled gender pay gap disappeared — meaning women and men with the same job title and qualifications were paid equally — the uncontrolled gender pay gap would persist as higher paying positions are still disproportionately accessible to men compared to women.

Women of color can face increased barriers in opportunity as gender and racial biases can intermix to create obstacles to hiring, pay raises, referrals, promotions, and leadership. Due to the social expectations placed upon women to be mothers and caretakers, women often step out of the workforce and are penalized when they return to their careers. The overall differences in women’s and men’s pay and career outcomes goes beyond gender preferences and can only be explained holistically through gender and racial bias.

Race and the Gender Pay Gap

Intersectionality creates larger pay gaps for women of color

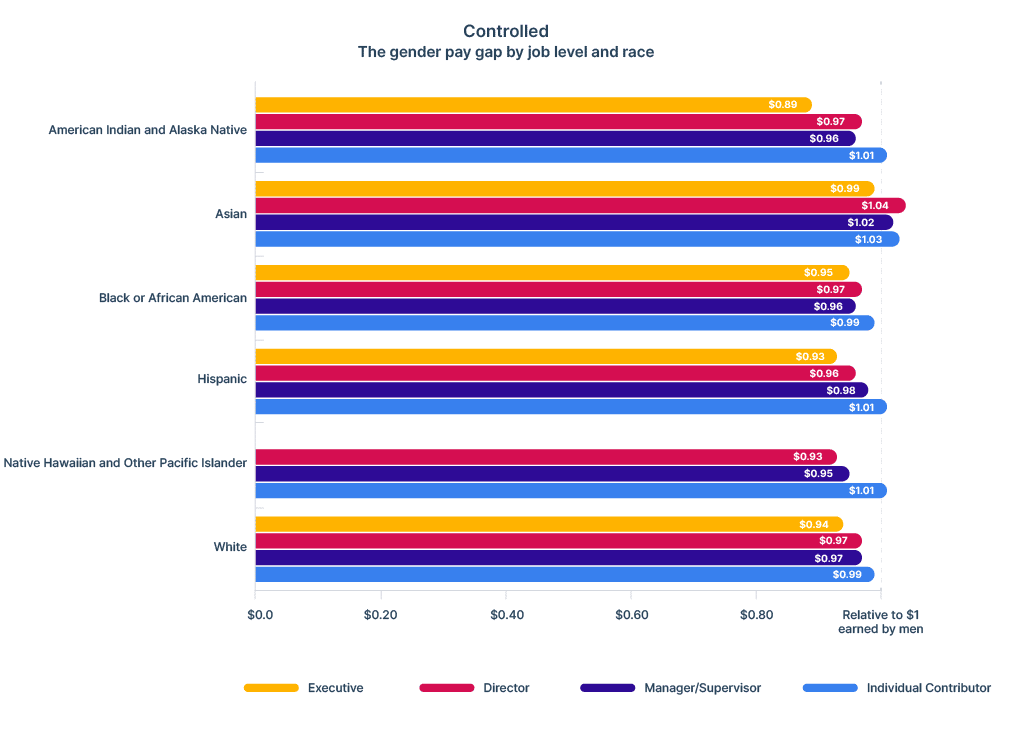

Race and gender intersect to result in wider pay gaps for women of color. For the uncontrolled gender pay gap, American Indian and Native Alaskan women (who make $0.71 to every $1 white men make) and Hispanic women (who make $0.78 for every $1 white men make) have the widest gender pay gaps. When data are controlled for compensable factors, Black women have the widest gender pay gap ($0.98).

What this means is that American Indian and Native Alaskan women and Hispanic women are more likely to occupy lower paying jobs. Black women are most likely to be paid less despite having the same level of experience and other compensable factors as white men doing the same job.

Only Asian women make comparably more than white men when data are controlled for compensable factors ($1.03 to every $1 white men make). This has been consistently true for years and a propagator of the “model minority” stereotype that assumes Asians are smarter, better educated, or harder working than other people, which can be used to discount racism against Asians. The model minority myth also fails to acknowledge that Asians are a diverse population and that some Asian minorities experience wider pay gaps than the general Asian population.

The Motherhood Penalty

Women who are parents experience a larger pay gap

Our gender pay gap analysis shows that women who return to the workforce after having children incur a wage penalty. In our online salary survey, we asked respondents to identify if they were a parent and leveraged this sample to analyze the pay gaps amongst men and women with or without children. The wider gender pay gap amongst women with children compared to those without children is called “the motherhood penalty” or “childbearing penalty.” When women indicated they were a parent or primary caregiver, we observed an uncontrolled pay gap of $0.74 for every dollar earned by a male parent. When we hold all else equal, mothers earn $0.98 for every dollar earned by fathers with the same employment characteristics.

Conversely, the gender pay gap shrinks considerably between men and women who are not parents. The uncontrolled pay gap reduces to $0.88 on the dollar, suggesting women without children face fewer social barriers in climbing the corporate ladder or securing demanding, higher-paying jobs (despite mothers being just as capable). When we control for job characteristics, we observe pay parity in our sample. Earnings of women without children keep pace with earnings of men without children. This supports research that suggests that having a child is the primary or true cause for the gender pay gap.

There are a range of disadvantages that impact wage progression for mothers. Research shows women’s income decreases because they (more than men) reduce their working hours to balance childcaring responsibilities. Women also face biases that working mothers are less committed to their work, which can inhibit career progression. Meanwhile, some men are paid more after having children.

As we detail below, the opportunity gap widens as women progress through their career – with 60 percent of women over the age of 45 occupying individual contributor roles compared to 45 percent of men in the same age group. Likewise, we measured just 4 percent of women in executive positions compared to 8 percent of men. Since the uncontrolled gender pay gap shrinks amongst women without children, we can point to motherhood as a powerful variable in career progression for women.

The Unemployment Penalty

The longer people are unemployed, the lower their wages when they return to work

The unemployment penalty illustrates the percentage difference in pay experienced by an individual (regardless of gender) who is currently employed compared to one who is unemployed, all else being equal. We see that this penalty becomes more severe the longer the unemployment period continues. Economists refer to this phenomenon as ‘unemployment scarring’, given the body of evidence that show interruptions to employment have both an immediate and sustained negative impact on earnings.

Observations of the gender pay gap indicate the unemployment penalty is generally more severe for women than it is for men. Among those who have been unemployed less than 3 months the gender pay gap is $0.83 on the dollar, but this widens to $0.70 when that period is more than 24 months.

Even when we hold all else equal between men and women, the controlled pay gap widens the longer unemployed individuals are actively seeking a job. After actively seeking a job for 18-24 months, the controlled gender pay gap is $0.95 for every dollar earned by men with the same employment characteristics.

In our analysis of the unemployment penalty and gender pay gap by employment status, we restrict the sample to those who were unemployed for reasons other than career development. The wider gender pay gap in this sample illustrates that even when men do leave the workforce for reasons other than schooling or training, they still maintain an advantage when they return to the workforce from being unemployed and receive higher job offers.

When asked to report the primary reason of unemployment in our online salary survey, 85 percent of those who reported that they were caring for a child were women – compared to just 15 percent being men. Women also reported caring for a family member other than a child at twice the rate of men. The gender pay gap, both controlled and uncontrolled, was widest for these groups among any other reasons for unemployment.

Women, black, indigenous and people of color have been disproportionately impacted by unemployment. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) data shows more women than men left the workforce due to unavailability and family responsibilities, in both 2020 and 2021 – a trend that is being termed The COVID Motherhood penalty.

The Gender Pay Gap by Age

Women lose earning power as they age compared to men

Women do not start their careers earning as much as men and the pay gap only widens as they age. Between the ages of 20 and 29, women earn $0.86 compared to every $1 that men earn. This is due to women being employed in jobs that do not pay as much compared to the jobs that men occupy. When controlled for job title and other compensable factors, women and men earn equal pay in the 20-29 age bracket.

However, the pay gap widens for women between the ages of 30 to 44, with women overall earning $0.82 compared to every $1 men earn. When controlling for job title and other compensable factors, women earn $0.98. At age 45 and older, the gender pay gap widens further for the uncontrolled group, with women making only $0.73 compared to every $1 men make.

The Gender Pay Gap by Job Level

The Gender Pay Gap by Job Level

Women are paid less than men as they move up the corporate ladder

Payscale’s gender pay gap research shows that even when women make it to the top rungs, they make less than their male counterparts. Women are also underrepresented in leadership roles, which can reinforce ideas that women do not make good leaders. This is why diversity in leadership is important alongside equity.

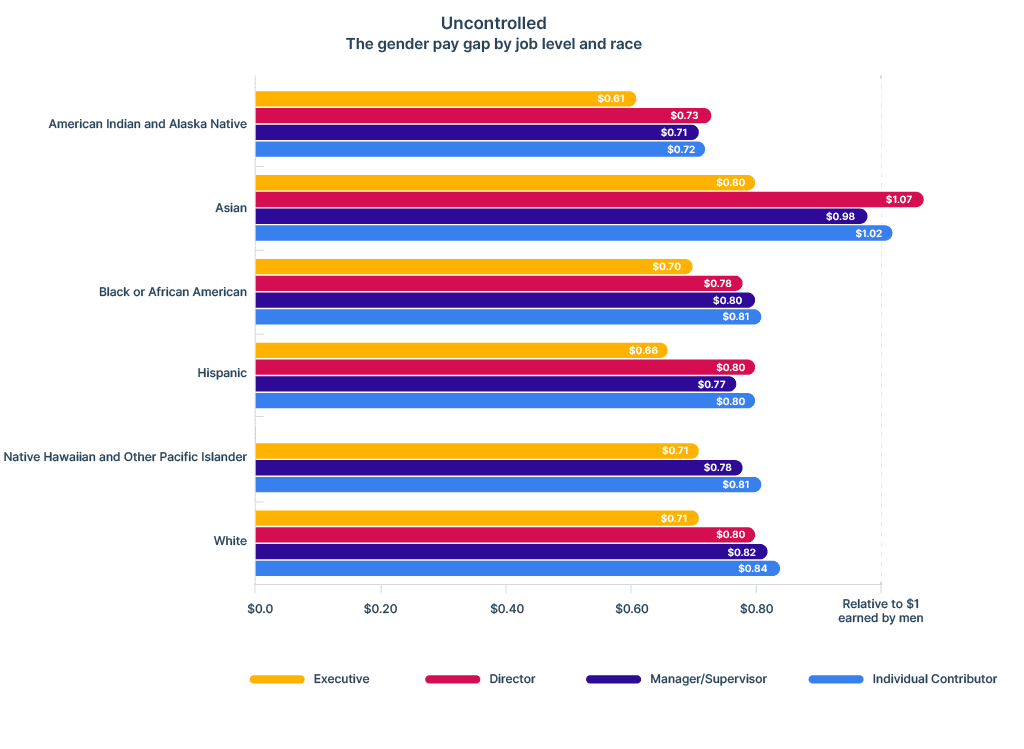

Women of every job level (individual contributors, managers, directors, and senior executives) make less than men of the comparative job level, but the gender pay gap widens as women progress up the corporate ladder. Women at the executive level make $0.95 to every dollar a man makes even when the same job characteristics are controlled for. In the uncontrolled group, women executives make $0.73 to every dollar a male executive makes. This is an improvement of $0.03 since last year in the uncontrolled group and $0.01 in the controlled group, which still isn’t much to cheer about.

Women aren’t promoted as often or as quickly as men

Men are also disproportionally promoted faster and more often than women. Why? One reason is that women can be pushed into performing work that is “non-promotable” such as party planning, volunteering, or routine maintenance work that isn’t necessarily compensable or celebrated by the business. Women can also be consciously or unconsciously blocked from networking and the visibility necessary to be considered for promotions or discouraged from displaying personality traits like ambition or a strong opinion, vision, or purpose, which are often associated with leadership.

In other words, women are less likely to be promoted and paid equitably in leadership positions because of gender stereotypes. Women executives are more represented in industries such as nonprofits or educational institutions, which pay less than other industries, and where the mission of the organization is more associated with “women’s work.” As previously covered, it can also be assumed that women will leave the workforce to have children, which can cause them to be viewed as less worthy of investment.

Women of color see wider pay gaps as they advance in their careers

We also looked at the gender pay gap by job level when intersected by race and found that most women of color are more likely to stagnate in their careers than white women. All women of color except for Black women start out with controlled pay equity relative to white men at the individual contributor level, but as they progress up the corporate ladder, the gender pay gap widens. Black women individual contributors make $0.99 for every $1 white men make when the same job characteristics are controlled for, but only $0.95 as executives.

When data are uncontrolled, the differences in the gender pay gap across racial groups reflects the overall gender pay gap, with American Indian and Native Alaskan women suffering the widest gender pay gaps at $0.72 for every $1 white men make as individual contributors and a dismal $0.61 for every $1 white men make as executives. American Indian and Native Alaskan women executives also only make $0.89 for every $1 white men make when data are controlled.

We observe that some pay gaps for women of color have widened during COVID-19. For example, Pacific Islander women at the director level saw the uncontrolled pay gap widen ten cents from $0.83 in 2020 to $0.73 in 2021 and then widen again to $0.71 in 2022. When controlling for compensable factors, Hispanic women executives saw the pay gap widen from $0.97 in 2020 to $0.94 in 2021 and now to $0.93 in 2022. These are larger fluctuations in the gender pay gap than seen in typical years.

Women of color see the least opportunity to advance

White men are more likely to be managers, directors, or executives than women of color, who are more likely to be individual contributors. Sixty-six percent of Black or African American women and 67 percent of Hispanic women are individual contributors compared to 62 percent of white women and 59 percent of white men.

The opportunity gap offers a key insight into workplace racial bias for Asian professionals, who lag dramatically behind other groups in attaining leadership roles despite higher earnings in general. Asian women are most likely to be individual contributors at 74 percent. Although Asian women are closer to pay equity with white men than white women overall, only two percent of Asian women make it to the executive level while four percent of white women did.

The Gender Pay Gap by Education

Women are paid comparatively less than men the more educated they are

Higher education does not lead to pay equity. The gender pay gap sees minimal or no improvement at higher education levels compared to a high school degree, which has a controlled pay gap of $0.98. While Associate’s degrees, Bachelor’s degrees, Master’s degrees (non-MBA), and Law degrees close this gap slightly at $0.99, MBAs see a wider controlled gender pay gap of $0.97 and Doctorates see an even wider gap of $0.96.

The largest uncontrolled gender pay gap is for those with MBAs. Women with MBAs take home $0.76 for every dollar that men with an MBA take home, which is commiserate with last year. This may be indicative of women struggling to get jobs requiring — and compensating for — an MBA compared to men. Women with a law degree see the smallest uncontrolled gender pay gap, although still substantial. Women with law degrees earn $0.89 for every dollar earned by men with a law degree.

The Gender Pay Gap by Industry

Bias against women in male-dominated industries perpetuates the gender pay gap

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), women are more heavily represented in industries such as healthcare (76 percent), education (69 percent), and nonprofits (65 percent), which – not coincidentally – are more aligned with gender stereotyping that women are best suited to be care givers and nurturers.

The uncontrolled gender pay gap is widest in Finance & Insurance ($0.77) and Agencies & Consultancies ($0.83) both of which have a higher percentage of women than men (53 percent) but where gender stereotypes that women aren’t best suited to math or problem solving may work against women in these industries. The industry with the largest controlled gender pay gap is Transportation & Warehousing ($0.96), which is an industry that may be prone to discrimination against women based on preconceived notions about their ability to lift and haul compared to men.

When controlling for compensable factors, Technology, Engineering & Science, Real Estate, and Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation achieve pay equity. These are industries that are at least somewhat dominated by men, though not as much as Construction, Energy & Utilities, Transportation & Warehousing, and Manufacturing, where gender pay gaps are wider.

The Gender Pay Gap by Occupation

Bias against women in “masculine” occupations perpetuates the gender pay gap

Occupation refers to the jobs that women do regardless of the industry. Women are most heavily represented in Healthcare, Education, Personal Care Services, Office Administrative Support, and Community and Social Service-related occupations. All of these occupations align to gender stereotypes that women are best suited for care and service to others.

Payscale’s research on the gender pay gap shows women are paid less than men in every occupational group we examined, with the widest uncontrolled gender pay gaps being in the fields of education ($0.75) and law ($0.63), indicating that women are more likely to be employed in lower paying positions even in occupations where they are dominant. The smallest uncontrolled gender pay gaps are in Healthcare Practitioners and Healthcare Support, where women dominate the field most significantly.

When data are controlled, the gender wage gap for 2022 closes for occupations in Architecture & Engineering, Legal, Education and Training, and Personal Care Services. Women in these sectors earn $1.00 for every dollar earned by men when controlling for compensable factors. The occupations with the widest gender pay gaps when compensable factors are controlled include Farming, Fishing & Forestry ($0.89), Installation, Maintenance & Repair ($0.94), Construction & Extraction ($0.95), and Production ($0.96).

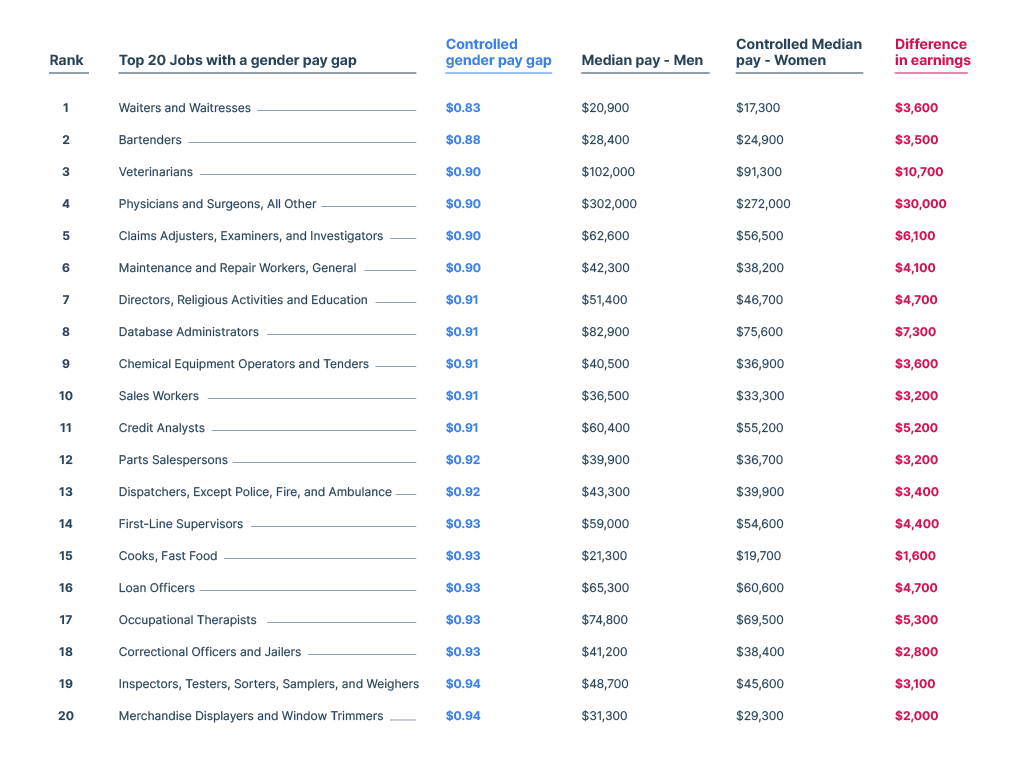

Top Jobs with Gender Pay Gaps

Ranked list of job titles with the widest pay gaps show the impact of lost earnings

To illustrate the impact of the gender pay gap in concrete terms, Payscale looked at the top 20 specific jobs with the largest gender pay gaps. The following list shows the gender pay gap when all compensable factors are controlled, meaning that women in these positions have the same qualifications as men in the same positions. All of these jobs show a wage gap wider than the $0.98 for the controlled group overall. Some of the positions with the highest gender pay gaps fall into occupations that are traditionally dominated by men or are subject to strong gender norms. However, there are also job titles here that do not clearly align to skills and responsibilities perceived culturally as more masculine or more feminine.

Methodology

Between January 2020 and January 2022, over 933,000 people in the U.S. took Payscale’s online salary survey, providing information about their industry, occupation, location and other compensable factors. They also reported demographic information, including age, gender, and race. We leveraged this sample to provide insights into the controlled and uncontrolled gender pay gap.

Analysis of the Racial Pay Gap

For analysis by race, we look only at those with at least a bachelor’s degree. Racial gender pay gap numbers reported are relative to white men unless otherwise noted. Due to sample size issues, we are unable to report data on Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders beyond the director level.

Unemployment and Parent Status

We also ask respondents to the survey about their unemployment status and if they are a parent. We provide these response rates overall, we also compare the GPG for different types of respondents. This sample was collected between June 2021 and January 2022 and comprised of 151,162 respondents to the Parent question and 55,090 respondents to the unemployment questions. These questions include:

Are you a parent or primary caregiver?

- Yes

- No

Are you currently employed?

- Yes, at this same company (They are evaluating a job offer at a company they already work for)

- Yes, but at a different company

- No

How long has it been since you were last employed?

- Less than 3 months

- 3-6 months

- 6-12 months

- 12-18 months

- 18-24 months

- More than 24 months

- This will be my first job

How long have you been actively seeking a job?

- Less than 3 months

- 3-6 months

- 6-12 months

- 12-18 months

- 18-24 months

- More than 24 months

What was the primary reason for your time away from work?

- I was attending school/receiving additional training

- I was caring for a child

- I was caring for a family member other than a child

- I was dealing with personal health issues

- I relocated

- I was let go from or quit my previous job

- Other

Definitions

Total Cash Compensation: TCC combines base annual salary or hourly wage, bonuses, profit sharing, tips, commissions, and other forms of cash earnings, as applicable. It does not include equity (stock) compensation, cash value of retirement benefits, or value of other non-cash benefits (e.g., healthcare).

Median Pay: The median pay is the national median (50th Percentile) total cash compensation (TCC). Half the people doing the job earn more than the median, while half earn less.

Uncontrolled Gender Pay Gap: Median pay for men and women are examined separately, and the difference in the median is reported as the uncontrolled gender pay gap. Variables such as years of experience and education are not controlled for. This provides a picture of the differences in wages earned by men and women in an absolute sense.

Controlled Gender Pay Gap: This is the amount that a woman earns for every dollar that a comparable man earns. That is, this is the pay difference that exists between the genders after we control for all measured compensable factors. If the controlled pay gap is $0.97, then a woman would earn 97 cents for every dollar that a man with the same employment characteristics.

Controlled Median Pay: To illustrate the gender pay gap, we calculate this estimate of what the typical woman would earn if she occupied the same position as the typical man.

Unemployment Penalty: This is the percentage difference in the salary offered to an individual who is currently employed versus one who is currently unemployed, while controlling for relevant factors and excluding those who were unemployed to attend school or receive additional training. The unemployment penalty changes based on the duration of unemployment.

Industries: PayScale uses 15 industry categories that are custom aggregates of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

Occupations: We report data for 22 occupations as defined by the Standard Occupational Classification System.

Job Levels

- Individual Contributor: Employees who do not manage others.

- Supervisors/Managers: Employees with people management responsibilities.

- Directors: Employees who manage managers, but are below the level of vice president.

- Executives: Employees with the title of vice president or hire.

Percent Men/Women (BLS): We present the gender breakdown by job group or industry according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics Current Population Survey from January 2022. For Industries, we calculated a weighted average of the custom PayScale aggregations of the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) groups when definitions span multiple NAICS industries (e.g. Technology).

Lifetime Earnings:

Lifetime earnings is the sum of median pay from each year, over 40 years, where each year the median pay increases by 3 percent. This is because 3 percent has been found in previous research to be a standard annual increase in base pay by the majority of employers.

Race/Ethnicity: Respondents could choose one or more of the following and could opt to self-identify in a open-response.

- American Indian and Alaska Native

- Asian

- Black or African American

- Hispanic

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander

- White

- Prefer Not to Answer

Only respondents who chose exactly one of the above were included in our analysis of the gender pay gap by race.

Close pay gaps with pay equity

In our annual Compensation Best Practices survey, Payscale asked employers about the gender pay gap within their organization and their commitment to pay equity. Employers are now embracing the mandate to provide fair and equitable pay and recognizing the moral and business advantages of doing so. This downloadable asset includes data and insights revealing trends on pay equity and what employers are doing to address pay gaps within their organization.

Download report